Article published in Sustainable Plastics by Amanda Martin and Ana de la Cal from Net Zero Chemistry.

The EU’s draft of the new End-of-Life Vehicle (ELV) Directive aims to spur the transition to more plastics circularity in the automotive industry. Currently, the lack of circularity in design and production mean that valuable resources are being lost from the production cycle.

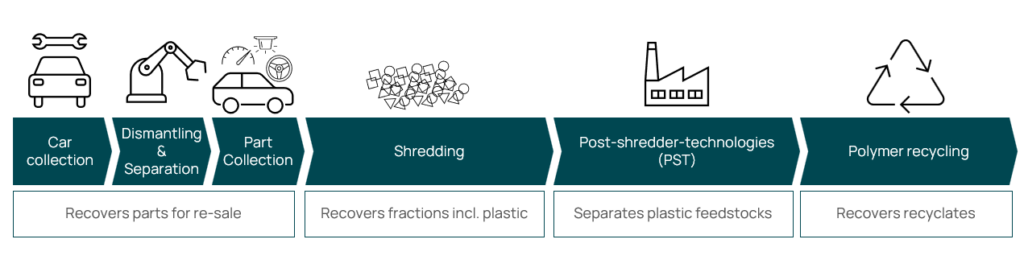

Increasing plastics recycling rates can be achieved by improving ELV dismantling and shredding practices as well as using more monomaterials. Getting there, however, is a challenge.

In 2000, when the ELV Directive was adopted, it established for the first time a harmonised EU framework that was designed to ensure that the disposal of vehicles reaching the end of their life was carried out in an environmentally responsible way. The new regulations contained provisions on ELV collection and depollution, i.e., the removal of the hazardous materials, and restricted the use of hazardous substances in new vehicles.

Importantly, the Directive also specified reuse and recovery targets of 85% and 95%, respectively, based on the average weight of ELVs per vehicle and year. As a crucial component of the EU economy, the automotive manufacturing sector heavily depends on primary raw materials such as steel, aluminium, copper, and plastics, while using minimal recycled materials.

In 2005, this legislation was expanded with a further EU directive on the type-approval of motor vehicles with regard to their reusability, recyclability and recoverability, known as the 3R type-approval Directive. It is part of the type-approval framework 10 under which new vehicle types are tested and granted type-approval before being placed on the EU market, provided they meet a set of technical requirements. This Directive’s design provisions state that vehicles should be constructed so as to be 85% recyclable or reusable and 95% reusable or recoverable.

From Recycling to Circularity

These Directives sought to improve the practices of the times, and to some extent, appeared to be successful. Certainly, the recycling rates rose. Yet, while recycling rates may seem high, they often mask underlying challenges. For example, Eurostat reported that in 2021, the EU’s reuse, recycling, and recovery rate for ELVs was 88%. This impressive figure suggests that the recycling of vehicles is on track. However, a deeper look reveals that these rates are primarily based on the weight of materials recycled, which mostly includes heavy metals, with limited attention to lighter-weight plastics. The present process treating end-of-life vehicles primarily results in lower-quality scrap metal with limited plastic recycling.

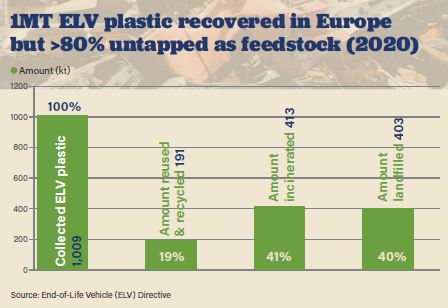

Moreover, the EU’s definition of “reuse, recycling, and recovery” includes incineration for energy recovery, meaning that incinerated plastics are counted toward the total recycling rate. In Europe, only 19% of ELV plastics are recycled each year, while 41% are incinerated for energy and 40% end up in landfills. With over six million vehicles reaching the end of their life each year in Europe, millions of tonnes of valuable materials are lost to the economy annually.

It became clear that a revision of the Directive was necessary to boost the transition of the automotive sector toward a circular economy. New rules were needed to promote the reduction of the environmental footprint associated with the production and end-of-life treatment of vehicles, increasing recycling of all materials, even lighter weight plastics. In July 2023, the European Commission unveiled its proposal for a Regulation on circularity requirements for vehicle design and on management of end-of-life vehicles, intended to replace the two earlier pieces of legislation.

Read the full article here.

SEE HOW WE’RE WORKING TO ADDRESS THE BARRIERS TO AUTOMOTIVE PLASTICS RECYCLING IN OUR PROJECT.